Safety Without Understanding: Lessons from Waymo

Recent safety statistics show us that safe self-driving has arrived. But how did we get here, and what lessons can it teach us?

Ten years ago, many argued safe deployment of self-driving cars was impossible.

Five years ago, self-driving cars were “always 5 years away.”

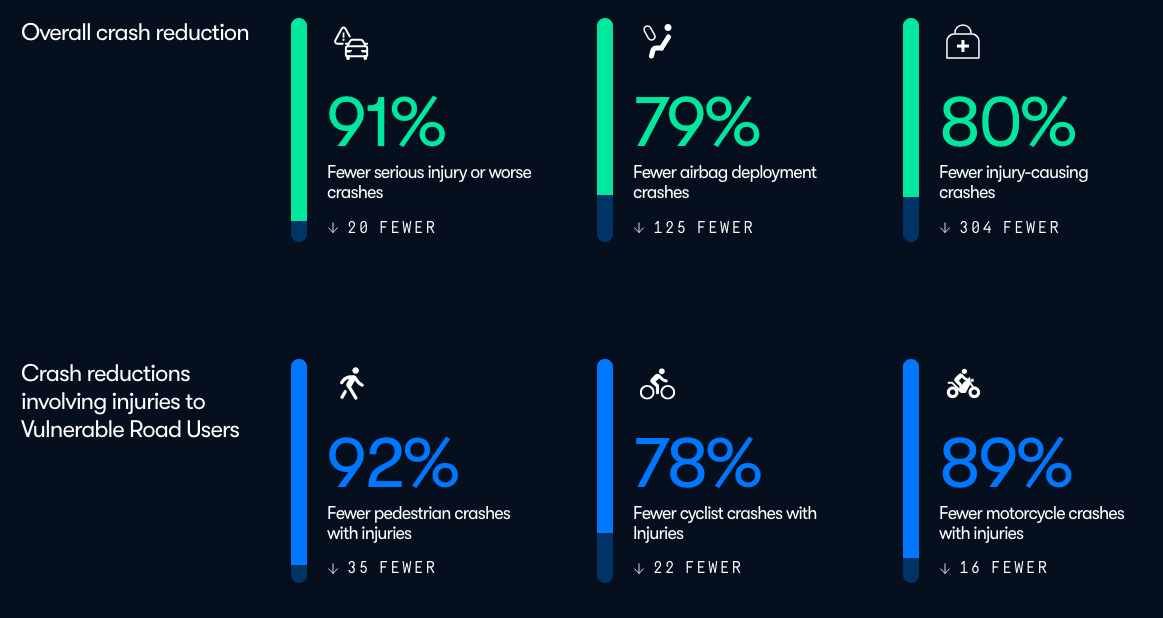

Today, Waymo operates in five cities and reports substantially lower crash rates than human drivers.

Waymo is not a traditional aerospace or manufacturing-style autonomous system. Gone are the systems of pure physics from which we can extract mathematical safety guarantees—Waymo lies in the murky world of neural nets and human behavior. And despite a huge amount of research effort, we’ve made little headway in squeezing a similar understanding from these new systems.1

Yet the safety statistics speak for themselves—Waymo is the first large-scale, safety-critical autonomous system that succeeds without deep mechanistic understanding. In a world that’s trending towards more autonomy and less explainability, it’s critical to examine how they achieved this, and the extent to which their strategy can be applied beyond transportation.

Waymo’s Safety Strategy

Throughout Waymo’s history, it’s had a remarkably good safety record, especially when compared to competitors like Cruise (effectively shut down after an accident and coverup) and Tesla (constantly in the crosshairs of regulators for their autopilot software.)

Perhaps non-coincidentally, Waymo is remarkably transparent about their safety strategy, which is laid out on their website. These documents make it clear that Waymo’s approach is deliberately multifaceted.

Thinking from first principles

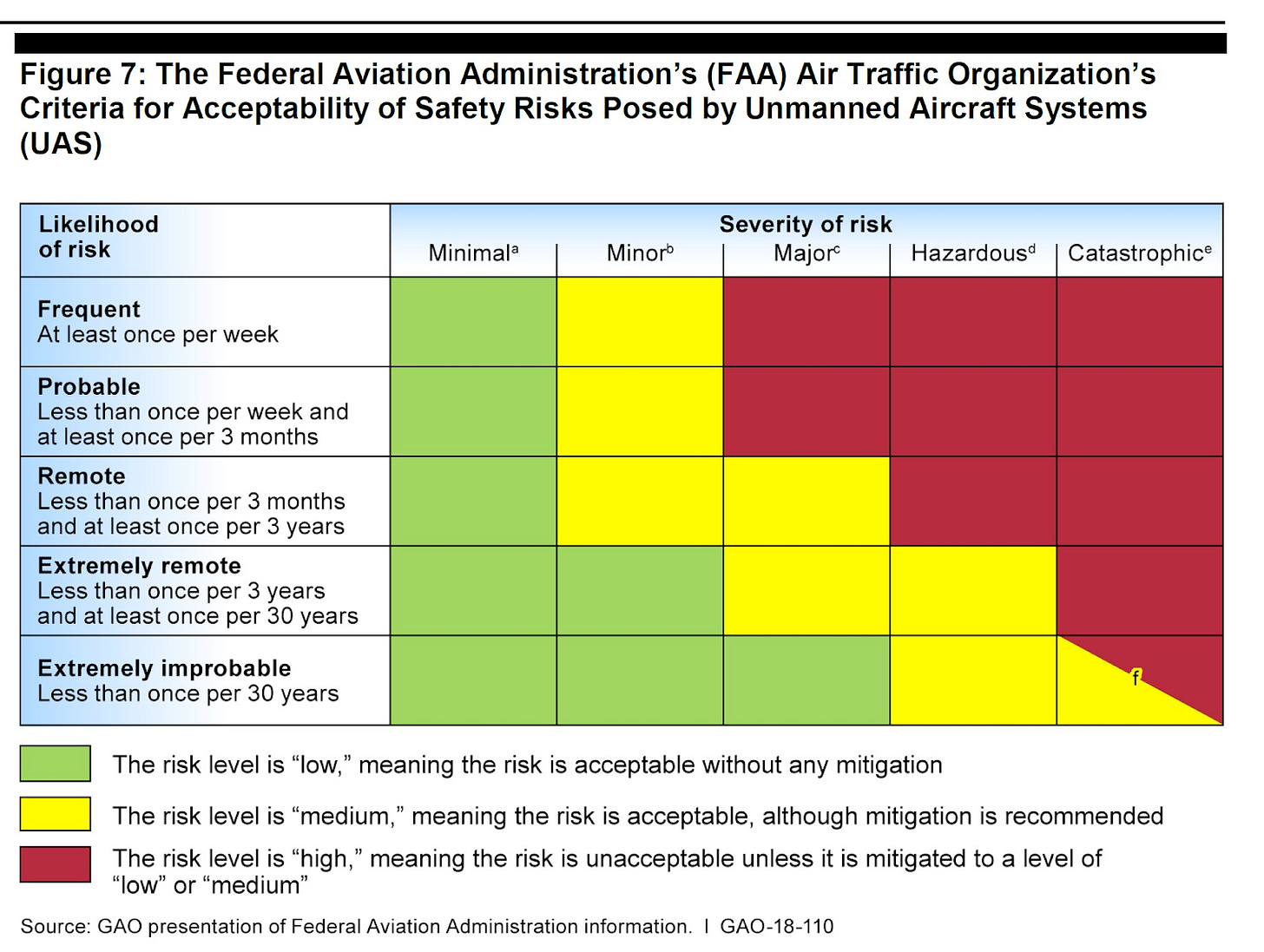

The first layer of defense is simply thinking deeply about the system and addressing the most obvious failure modes. Some of these approaches are highly traditional, like relying on redundancy for critical actuators and performing aerospace-style “hazard analysis,” where engineers brainstorm and subjectively rank the top risks in their subsystems, and recommend them for mitigation or tracking.

They also reference more modern evolutions of these ideas like System Theoretic Process Analysis (STPA), which takes a structured approach to uncovering hazards which could arise from system interactions, with a special focus on feedback loops and control.

Testing in simulation and in controlled environments

These first-principles approaches uncover potential risks—they then need to be thoroughly tested to ensure they’re addressed.

To that end, the identified risks (i.e. a pedestrian running into the street, a brake failure, etc.) are turned into thousands of scenarios which are exercised on closed courses or in simulation. Combine this with a Monte Carlo approach, where you run and verify hundreds of variants of the same simulation with slightly different parameters, and Waymo can achieve test coverage which would take billions of miles to achieve in the real world.

Testing with real-world data

Simulation provides scale, but testing with real-world data gives the results credibility. This occurs at three levels of fidelity.

The lowest level of fidelity is testing new software against old driving logs. This approach is highly scalable, but is complicated by the inherent need for some level of counterfactual simulation. How would the other agents in the environment have acted if the car had indeed taken this new set of actions, rather than the ones taken by the old software? These simulations are only as useful as the model of human behavior used to run them.2

At a medium level of fidelity, Waymo uses a strategy which they call “public roads driving with counterfactual simulations,” where new software is deployed on real roads but with a human driver. Here, the simulation burden is much lower—one only needs to counterfactually simulate the rare portions of the drive in which a human driver takes over.

The highest level of fidelity is of course a real gradual deployment of new software, but this is by far the least scalable option.

And this is… basically it, at least according to public sources. It’s useful to pause and reflect here for a second.

There are no physics-informed neural nets.

There are no mathematical guarantees that AVs maintain a safe distance from other users.

There are no efforts to understand or bound the behavior of neural networks at a low level.

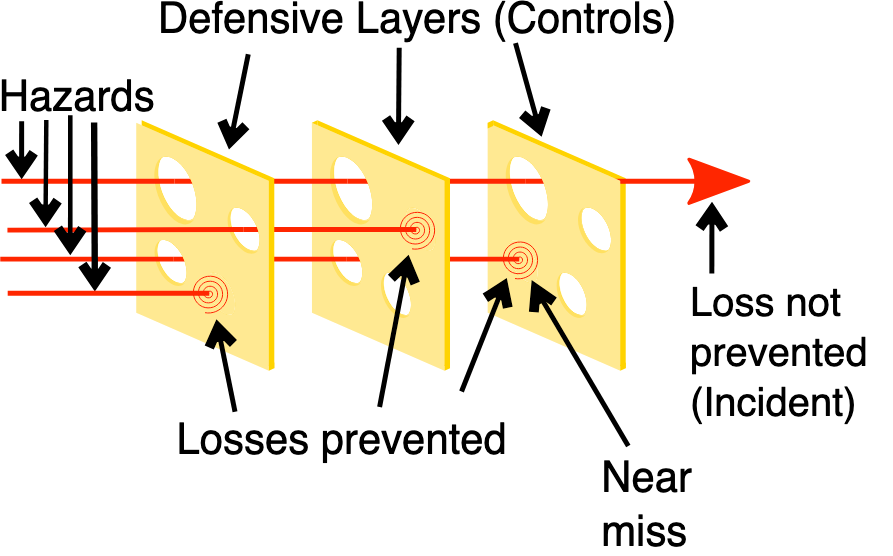

There is no “secret sauce” to safety. All that there is is a strong safety culture, a very good simulation, and a huge variety of common-sense tests. This is sometimes called a “Swiss cheese” approach—as more and more tests are added, the chance of a failure mode going undetected approaches zero.

But this simplicity should not be mistaken for triviality.

The Catch

There may not be a special sauce, but there’s certainly… a lot of sauce. For one thing, developing a trustworthy simulation is a massive, resource-intensive operation. The following tidbit from Waymo’s safety framework is representative here:

Waymo uses closed course testing to ensure that various assumptions used in our simulation model are in fact accurate … [for example] we need to know that the simulation replicates the actual performance of our AV using the same braking profile.

This sounds hugely expensive—to ensure safety, every behavior tested in simulation needs to be painstakingly validated in the real world, on a closed course!

To make matters worse, a significant part of Waymo’s technical stack relies on creating detailed maps of the domains in which they operate, and using that to supplement perception. This means that a detailed simulation is necessary not only for safety but also for performance.

Herein lies another “catch”—the need to significantly limit the operating domain of the system. When rolling out to a new area, one needs to first gain the ability to simulate it accurately—the fact that one can use this to improve the safety of the system is almost a bonus. In this way, the very thing that makes Waymo so safe is what limits the speed of its rollout and the applicability of its safety process to other industries.

The final piece of this puzzle is the regulatory one, which could undoubtedly fill a blog post on its own. (At a high level—Waymo can be legally responsible for accidents caused by its cars, must report any crashes to the DMV, and is implicitly accountable to the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration.) How much of Waymo’s responsible approach was shaped by the looming threat of regulatory action, and can other companies hope to follow in their footsteps without similar external pressure keeping competitors in line?

Beyond Cars: Where These Conditions Hold (and Don’t)

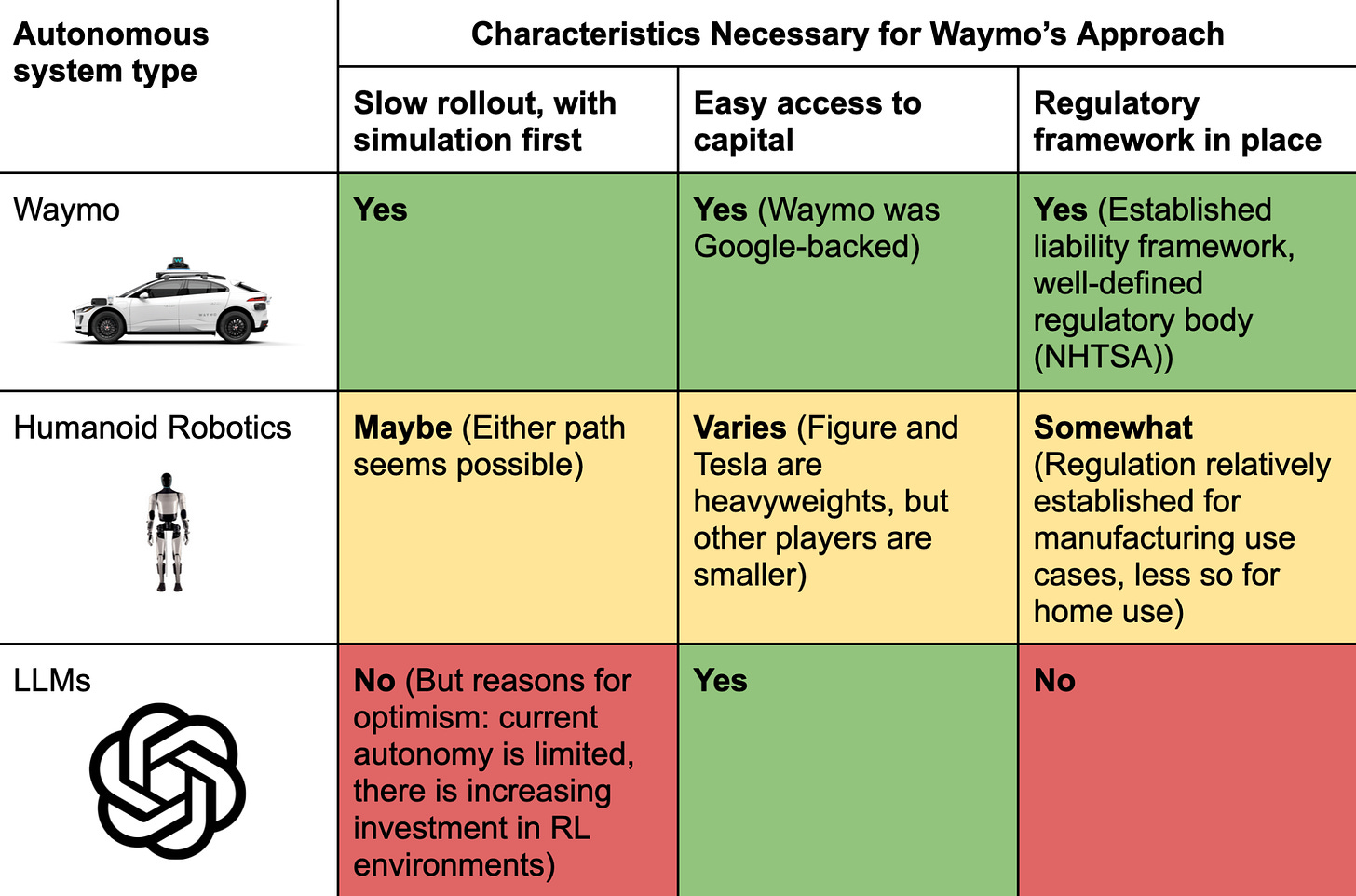

Waymo serves as a living example that safety can be achieved, even for systems which defy understanding. But the conditions which allowed Waymo to take this path are by no means universal. It’s worth exploring how these map to other industries which are expected to be significantly autonomous in the near future.

Humanoid Robotics

Humanoid robotics are an especially interesting case study, because it seems that the technology is at a branching point. Which path the field takes will largely determine whether Waymo’s approach applies.

The vanilla case for robotics looks a lot like Waymo—deployment on a task follows data collection and simulation, rather than the reverse. Task-specific data remains a stubbornly necessary part of making robots work in the real world. It can be challenging to develop working robotic policies from pure simulation even in narrow domains, because subtle differences between simulation and reality can result in policies failing to generalize to reality.

Tactile manipulation is one such area that proves difficult in practice—the subtle physical interactions that govern even “picking something up” are poorly understood. Our best approach to these problems has historically been “painstakingly record a bunch of data about picking up this specific object.”

This world looks a lot safer, but also a lot more challenging for the economics of the industry. Mapping the location of every stop sign in San Francisco is tough—mapping every object in every home in America is much tougher.

For this reason, the robotics industry is pushing hard for another path. The holy grail is a “robotics foundation model” of sorts—a pretrained model which can be seamlessly dropped into any environment and accomplish tasks with minimal task-specific fine-tuning. While this would be a game-changer for the industry, this scenario risks incentivizing a broad rollout without the necessary safety infrastructure in place. We’d need a concerted effort and innovations in simulation to use Waymo’s approach here, but if robotics takes a more default path, the safety problem seems quite tractable.

LLMs

A more stressing case study for Waymo’s strategy is that of LLM-driven autonomous agents. This is also a more important case study, because LLMs will likely make up the majority of autonomous systems going forward (including the “brains” of robotic systems!)

The most notable disanalogy between LLMs and autonomous driving is that LLMs have not followed the path of simulation preceding deployment—the vast corpus of internet pretraining data allowed them to be widely deployed before any real simulation capabilities existed.

This doesn’t seem like a fundamental property of LLMs, but rather the path of least resistance. In some sense, typical LLM environments are far easier to simulate than the real world—we just haven’t made it a priority yet. Unlike the physical world, web-based environments and text conversations can be losslessly stored and replayed later, bypassing the “simulation to reality gap” that plagues robotics software.3

We’re at a critical juncture to take advantage of this property—despite LLMs being widely deployed, we’re still in the infancy of truly autonomous LLM agents. As systems become more autonomous (and perhaps as a result of this shift), RL simulation environments for LLMs are gaining traction. Just like Waymo, using these simulation environments to ensure that our current-day models are robustly aligned can provide us a solid foundation to build on.

Looking forward, the real crux of the problem is whether future models will be smart enough to game such tests, rendering them ineffective. But there’s reason to think that this is avoidable as long as researchers avoid doing things like optimizing directly for performance on safety benchmarks. It feels legitimately plausible that “being dangerously misaligned” lies much, much lower on the capability scale than “being dangerously misaligned and also contorting yourself enough to obscure this fact in hundreds of unique tests.”

Some AI companies seem to be taking a Waymo-style approach seriously—Anthropic’s recent post on “putting up bumpers” advocates for exactly this kind of layered testing. Waymo muddled through setbacks and significant uncertainty to arrive at a system which is legitimately safe and superhuman. Perhaps we can do the same with LLMs.

A Path Forward is Possible

Waymo is not only a picture into the future of transportation, but also into a framework which can be used to make autonomous systems safe going forward.

What strikes me in their approach is its simplicity. Layer many common-sense defenses on top of one another, and where one fails, another likely will not. Layer enough of these tests on top of one another, and the probability of failure asymptotically approaches zero.

But despite not relying on any fundamental breakthroughs, it levies significant requirements on companies which want to follow in their footsteps—deep pockets, a favorable regulatory environment, and significant engineering effort. These conditions are not replicated exactly in other industries, but two principles from Waymo’s success are particularly worth carrying forward broadly:

Simple safety strategies matter too!

Waymo didn’t wait around for academia to solve explainable AI—they forged ahead, slowly and methodically building a safety case with hundreds of small pieces of evidence.

Any successful alignment effort in the near-term will likely look similar. I’m not against moonshot research, but rather than sitting around waiting for mechanistic interpretability to save the day, researchers should get practical and think about tests that they can implement in the current world.

Acknowledging the power of these simple strategies, at least for near-term systems, can make things feel far more tractable and encourage more investment into safety.

If we’re going to invest more in safety, a promising area for investment is in improving simulations.

Waymo shows the power of simulation to derisk even black-box systems. But right now, our simulations are woefully insufficient—LLMs can see right through them, and simulating real-world edge cases is an expensive and manual process. We desperately need innovation in this area to create simulations which are both more realistic and more cost-effective (some ideas in footnotes.)4

The beauty of investing effort into simulation is that it can be dual use. Simulations are often primarily aimed at improving the capabilities of the system. With just a bit of focused effort, they can be just as big of a boon for safety.

At the end of the day, the story of Waymo implies that safety without deep mechanistic understanding is achievable—but not automatic. It requires deliberate investment in unglamorous infrastructure: thousands of test scenarios, painstaking simulation validation, and a genuine commitment to safety culture.

The good news is that we largely know how to do this. The question is whether we will.

This is not to say no progress has been made (i.e. work on circuit discovery or the iconic Golden Gate Claude saga), but it seems unlikely that models will ever yield to analysis the way that i.e. linear systems can be analyzed for stability by looking at their eigenvalues. My intuition is that complex systems often result in irreducibly complex explanations.

To make an RL analogy, we can think of this testing data as being highly off-policy, and thus more difficult to use effectively.

One complication that has recently made the rounds on Twitter is LLM’s propensity to understand when they being evaluated. But if bad behavior is observed in the wild, it seems like one can simply save these inputs and replay them exactly for a later model. To be fair, though, one can only seed a conversation in this way—much like Waymo’s “public roads driving with counterfactual simulations,” as soon as the LLM responds in a unique way, one needs to simulate continued responses.

For robotics: generative world models like Sora seem promising for reducing the manual engineering burden of simulation creation. Strategies like this could unlock automated edge-case testing and greatly improve safety.

For LLMs: we’ve already spent billions of dollars on a text-based simulation of one type of agent—humans! Prior to RL post-training, base models are effectively the most straightforward way possible to simulate human behavior in text-based environments. We can and should use them, likely with tweaks, to make interactions with humans much safer (see benchmarks like SpiralBench).